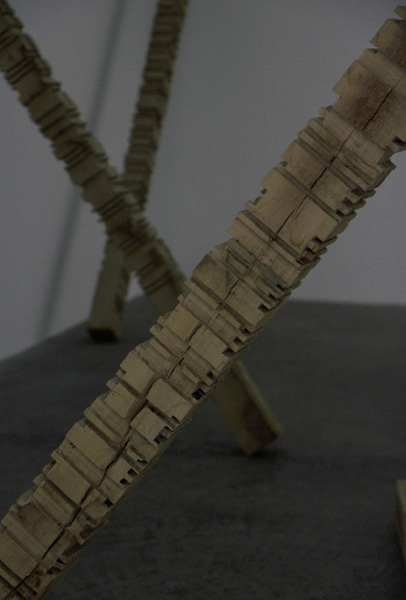

• Le crépuscule du matin. (Dans ce jour qui est presque nuit)[The morning twilight. (On this day which is almost night).] 2012 (variable dimensions) Figure littéraire singulière, Hélène Bessette a développé durant les années 1950/1960 une écriture hautement personnelle. Élaborant une oeuvre basée sur une langue anguleuse, sans confort ni bienséance, elle a très tôt fait fi de toute progression linéaire. Comme le dit encore Bernard Noël: “Cette écriture ne s’arrête pas, ne développe pas, n’habille pas, mais décharne, tranche, découpe. Elle n’a cessé de se dépouiller [pour que] ne compte que l’énergie, qui précipite les mots pour donner forme à l’action mentale”. Cherchant à explorer quel impact physique un texte peut avoir tant sur une matière que sur le spectateur, il le traduit et l’encode à même nos perceptions. Utilisant la plasticité propre à la langue de Bessette, il la fait ronger les fondations de notre imaginaire. Ainsi le spectateur se déplacera-t-il dans les soubassements affaiblis du langage, au rythme de ce texte même. Mêlant dans une approche sculpturale matériaux naturels (chêne, pierre) et lumière par un habile jeu de hors-champ, Emmanuel Lagarrigue délivre une installation à l’apparente simplicité, au calme trompeur. Appelé à déambuler dans un paysage aux formes entaillées, le spectateur circule dans le même temps dans l’espace de la langue et dans celui de son expérience. Les six poutres en chêne sont entaillées par 6 extraits du «Bonheur de la nuit» d’Hélène Bessette traduits en morse. Chaque poutre propose un «quatrain» dont chaque ligne correspond à l’une de ses faces. 1: Et il parle. / Voix lointaine, monocorde. / Ils parlaient tous, seuls. / Tous. Tout seul. A singular literary figure, Helene Bessette (1918-2000) developed a highly personal writing style during the 1950s and 60s. Elaborating a body of work with an early disregard for any literary progression, based on a sharp use of language without comfort, nor decorum. As Bernard Noel has again stated: “this writing does not stop, does not develop, is not embellished but emaciates, cuts, carves up. It does not stop stripping back so that the only thing that matters is the energy that quickens the words to give form to the mental action. Searching to explore what physical impact a text can have as much on a material as on the spectator, he translates it and encodes it as well as our perceptions. Using the specific plasticity of Bessette’s tongue, Lagarrigue makes it eat away at the foundations of our imagination. In this way the spectator shifts around in the weakened underbody of language, to the rhythm of the text itself. In a sculptural approach that combines natural materials (oak, stone) and light with a clever offscreen game, Emmanuel Lagarrigue delivers an installation of apparent simplicity, of misleading calm. Called upon to wander in a landscape of cut forms, the spectator simultaneously circulates in the space of the language and in the space of their own experience. The six oak beams are carved with six extracts from Happiness of the night” by Hélène Bessette translated into Morse code. Each beam proposes a “quatrain” in which each line corresponds with one of its sides. 1: And he speaks. / Distant, monotonous voice. / They were all speaking, alone. / All of them. All alone. |  |  |  |  |  |